Down but Not Out: The Life of Eric Readinger and His Mother

Down but Not Out: is a beautiful memoir penned by Eric’s mother, Julianne Zedalis.

This is a guest blog with an introduction by a Madison volunteer, Julia Sullivan, and an essay by Julianne Zedalis. We are proud to help spread this message of connection and inspiration, in partnership with GiGi’s Playhouse San Diego and GiGi’s Playhouse Orange County, where Eric had attended events.

Introduction by Julia Sullivan

Beautiful stories can arise from the most unfortunate circumstances. My Uncle Tommy was one of my favorite people. He was a man who loved sharing stories, eating the best foods, cheering for his family, and connecting with others. In January 2025, he passed away surrounded by love. At his funeral, I had the privilege of meeting some of his wonderful friends. Among them was Julianne Zedalis, a retired teacher and wonderful mother who wanted to share her connection to my Uncle Tommy. Julianne’s son, Eric, and my Uncle Tommy became fast friends, bonding over their shared love of sports. Eric was an extremely accomplished son, friend, uncle, and brother with a captivating spirit. Although I did not get the pleasure of meeting him, it brought me great joy to learn about the friendship he shared with my uncle.

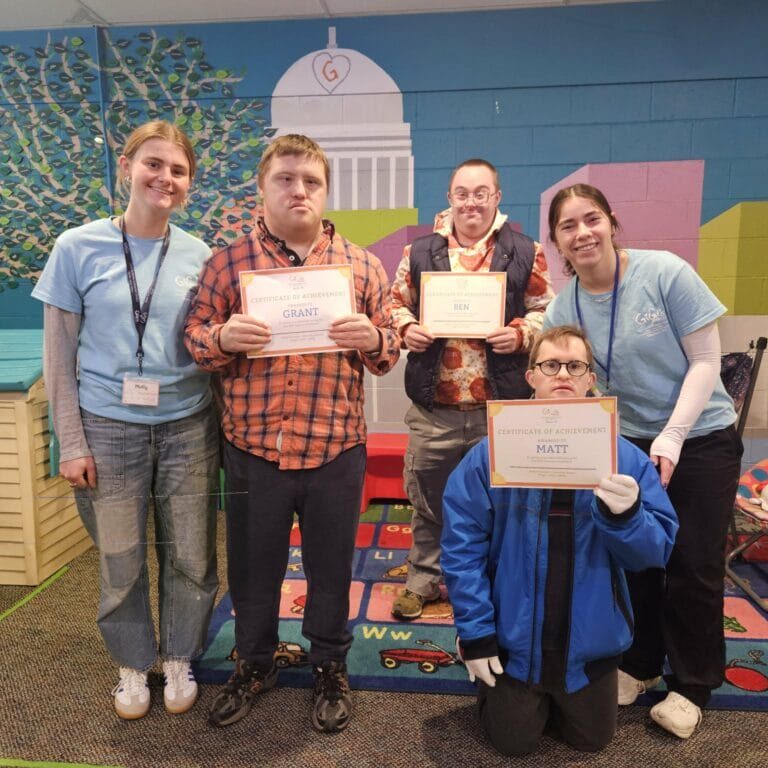

As a former volunteer at GiGi’s Playhouse in Madison, Wisconsin, I witnessed the tight-knit community that GiGi’s fosters. This community extends far beyond the walls of the playhouse. During my conversation with Julianne, we quickly discovered our connection to GiGi’s. Eric had Down Syndrome and was a frequent participant at GiGi’s Playhouse in San Diego and Orange County, California. Eric suddenly passed away in December of 2024. Julianne has dedicated her time to sharing Eric’s story, bringing hope, inspiration, and a smile to those who learn about Eric.

Currently, Julianne is writing a memoir, Down but Not Out, to share the invaluable lessons Eric taught her throughout his life. She has also beautifully written an essay that offers a glimpse into the life she and Eric shared together. Although Eric and my Uncle Tommy will be missed immensely, GiGi’s has led me back to a community where we inspire, encourage, and love one another.

DOWN BUT NOT OUT

A Teacher’s Lessons from Her Son

Julianne Zedalis

Before iPhones and iPads, I sat in the waiting room of a doctor’s office and had exhausted the supply of ubiquitous reading material, including Highlights for Children and Reader’s Digest. It would be another half hour before our family doctor could ensure that I had recovered from a recent bout of bronchitis. Although I had not coughed for days, my high school tennis coach required a note allowing me to return to the court, contagion-free. One patient shared the room with me—a silver-haired, eighty-something woman hunched over a tattered copy of National Geographic with an Egyptian sphinx on the cover. Restless and bored, I asked,

“Find anything interesting in that one?”

I soon regretted my sarcasm. Peering through her bifocals, and with a stronger voice than I had expected, the woman replied, “Everything is interesting.” She closed the magazine, and we began chatting. I was impressed by her elegance, charm, and more knowledge of myriad subjects than a Jeopardy! champion. When asked where she went to college, this great-grandmother of seven answered, “The world is my university.”

Little did I know that my greatest lesson would come in the form of a four-pound, premature infant with an extra chromosome whom we would name Eric.

The woman’s words echoed in my head. A stereotypical overachiever, in high school I participated in nearly every extracurricular activity offered, including student council and theater. The only blemish on my academic transcript was the B+ I received in a summer school drafting class. I had to settle for salutatorian, not valedictorian. In college, I sweated through History of Civilization crammed into a lecture hall with other first-year students, and celebrated when the 37% I earned on an organic chemistry test was at the top of the curve. I spent the first semester of my senior year in Rome researching the pros and cons of Italy’s national health service. After graduate school, I married a West Point cadet under a bridge of sabers, and spent three years as the wife of a second lieutenant assigned to a tank battalion in Germany at the height of the Cold War. While working as a chemist at a large Army hospital in Frankfurt, an ad in the Army Times caught my eye: a call for biology teachers at a satellite campus of the University of Maryland, a fateful event that triggered my forty-year teaching career.

After returning to the States, we started a family. While I had spent countless hours struggling to understand the dynamics of the Kreb’s cycle, no lecture or lab experiment had prepared me for the challenges of parenthood. On a cold afternoon in March 1980, Eric was born. What dreams we had for our son: an Ivy League college, a Heisman Trophy winner, maybe CEO of a Fortune 500 company. However, as spoken by Vincent, the lead character in the 1997 film Gattaca, “There is no gene for fate.”

I remember how the obstetrician averted his eyes when showing us the single crease across Eric’s palm and told us that our baby had Down syndrome. Down syndrome is a chromosomal disorder occurring in one in eight hundred babies. As we learned in our high school biology class, chromosomes contain DNA inherited from our parents that give us traits.

People with Down syndrome typically have 47 chromosomes instead of 46, the normal number. Most have an extra copy of chromosome 21 (trisomy 21). (World Down Syndrome Day annually occurs on March 21—the 21st day of the third month.) The extra genetic material results in certain physical features like a single palm crease and heart defects, and intellectual and developmental delays. Eric’s form of Down syndrome was rare: a translocation, in which an extra piece of chromosome 21 attaches to another instead of being separate. No behavioral activity of the parents or environmental factors are known to cause Down syndrome. It just happens.

I remember the stale cigarette breath of the elderly priest who stooped over my hospital bed and whispered, “Don’t worry, he probably won’t live very long.” I remember the colonel and his wife who sent a card with Our condolences on the birth of your baby scrolled above their names. My heart shattered when realizing that our son would never make the honor roll, star in a school musical, or play a varsity sport. In those initial hours spent in shock, sadness, denial, anger, guilt, and loss of faith, I remember the young Army chaplain summoned from Fort Knox who held my hand, looked at me in the eyes, and said, “Perhaps Eric is here to teach, not to learn.”

The lessons this teacher has learned are not found in the words of a scientific journal or textbook, and must be experienced first-hand. Eric’s world became my university, with him my master teacher. Surgeons doubted if the hole in his heart could be fixed. We knew the odds: Eric had a 5% chance of surviving surgery, but without it, he had a 0% percent chance of living. Eric not only survived the nine-hour surgery, but barely had a murmur forty years later. While recovering, he was placed in what was essentially a medically induced coma. One night I experienced the most powerful moment of my life. I sat at his bedside with tears streaming down my face and prayed for a sign that he was going to beat the odds. A nurse heard my sobs and insisted that I talk to my baby. “Sing to him,” she instructed. What? Why? The nurse pointed at Eric’s heart monitor. Every time he heard my voice, his pulse rate and blood pressure increased. My son recognized his mother’s voice! He responded in the only way he could. The next morning when I walked into his room, he was sitting up eating vanilla ice cream, his favorite!

Not only did Eric have much to teach his parents, he had much to teach the experts. We offered him the world, and let him limit himself. Defying a special education teacher who said that he wouldn’t walk until he was five years old, Eric took his first steps at fifteen months. At seven, he was able to do his own laundry, make his bed, and prepare a peanut butter sandwich for lunch. In middle school—and despite stuttering except when he sings, a phenomenon shared by Elvis and Ed Sheeran—Eric ordered twenty ham-and-pineapple pizzas from Domino’s but forgot to give our address. At least he made the call. Eric was suspended from school for three days by an unforgiving principal because he took an extra serving of spaghetti from the cafeteria. (You read this correctly. The principal considered taking another serving of anything theft.)

Eric spent hours wrestling with math problems until a creative teacher tapped into his love for sports that had ignited while watching his younger sister Kelly play soccer. Soon he could painstakingly calculate on paper that if his beloved San Diego (now Los Angeles) Chargers scored 21 points and the Kansas City Chiefs scored 14 points, the Chargers won the game by 7 points. Eric was introduced to technology by playing Oregon Trail on our Apple Macintosh computer, and his iPhone and iPad would become his favorite tech devices. He played a mean game of Wii bowling, and could manipulate the remote for his Smart TV better than the Geek Squad. Although his text messages were riddled with grammatical and spelling errors—can I by a carmal frapcino at Starbuks—he added the heart emoji when texting me that he loved me.

Eric earned three varsity letters in high school by managing the football, basketball, and baseball teams. At the end-of-the-year banquet, his football teammates voted him Most

Inspirational Player for perseverance in the face of adversity. His academic program consisted of special education classes in reading, writing, and math and inclusive electives such as art, theater, and cooking. Eric met every goal of his annual IEP (Individualized Education Program) and often exceed them. His woodshop teacher was a Scout leader for special needs students and introduced Eric to camping and white-water rafting. With confidence Eric asked the head varsity cheerleader to prom. He received a standing ovation from his classmates when proudly strutting across the stage to receive his equivalency diploma. Although restricted to my seat, I walked across the stage with him.

I envied my son. He had more friends than I will ever have because his cheerful disposition, innate kindness, and positivity invited conversation with those who had the courage to cross the barriers of discomfort. Eric was blind to IQ points, race, religion, and wealth. Supervised by a job coach from Partnerships with Industry (later PRIDE)—and until the Covid pandemic disrupted our lives—he worked full-time in the dining hall of a Point Loma Nazarene University stacking glassware, stocking the salad bar, and cleaning tables. The college students nicknamed him “E. Rock.” During summers, he worked independently with my school’s maintenance staff as they prepared the campus for the upcoming academic year. Eric spent his paychecks adding to his collection of sports memorabilia, Ray-Ban sunglasses, wrist watches, and treating his mom to a caramel Frappuccino at Starbucks. My son never walked past a person needing help without offering whatever cash was in his wallet or a sandwich from the bag of groceries he carried. Eric’s voice was the loudest when cheering for his young niece and nephew at their soccer and basketball games.

Eric possessed an incredible spirit for just living. He embraced the moment, neither haunted by past regrets nor burdened by future worries. While an A on a report card or a salary bonus reward our achievements, Eric was rewarded by the mere process of trying. He relished new opportunities and activities, even yoga at Gigi’s Playhouse despite the odd anatomy of his knees. Eric tackled jigsaw puzzles and enjoyed card games, beanbag baseball, and Wheel of Fortune and Family Feud on TV when not glued to ESPN cheering for the Chargers or San Diego Padres. Despite inherent challenges, people like Eric excel at what they can accomplish, from participating in sports through Special Olympics and community theater, attending college, holding down jobs, working out at local fitness centers, starring in TV shows like Glee, and lobbying on Capitol Hill for equal opportunities and health care. Some people with Down syndrome marry. Whatever extracurriculars Eric participated in, he participated with gusto.

My son taught me patience, to cheer for the underdog, and to realize that hardship and adversity bring out the best in us, or the worst. Eric showed me how to navigate the bumps and potholes we can encounter when taking the high road. He accomplished more than anyone could have imagined in that newborn nursery so many years ago. He reminded us that we all have disabilities; some are just more visible than others. Eric taught me that in the words of children’s author Robert Louis Stevenson, “Life is not a matter of holding good cards, but of playing a poor hand well.” My son played his hand well.

On December 1, 2024, Eric unexpectedly died in his sleep. His heart had beat its last beat. My son’s last words to me were “I love you, Mom.”

In my grief, I am reminded of the words attributed to Theodore Geisel, A.K.A., Dr. Seuss: “Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened.” My son made me a better teacher, and, more importantly, a better human being. The world became my university, and Eric would want me to continue to show up for class. I was blessed to have been chosen to be his mom.

About the Author

Julianne Zedalis recently retired from a 40-year career at Albuquerque Academy in New

Mexico and The Bishop’s School in San Diego where she taught Advanced Placement Biology and forensic science to high achieving students. A recipient of myriad awards, including the

Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Mathematics Teaching, she also worked for The College Board, writing the curriculum and exam for AP Biology. Julianne also contributed to several textbooks and supplemental materials for AP Biology. She and Eric moved from San Diego to Orange County, CA to be near her daughter Kelly and grandchildren, Isabella and Dylan. “Uncle E” loved cheering for his niece and nephew at their sports events. Julianne is the author of CS High, a STEM-based mystery novel for young adults, and is writing Down but Not

Out, a memoir based on the lessons she learned as Eric’s mom.

Recent Posts

New Year, Same FREE Programming!

Unique Ways to Support GiGi’s Playhouse Madison: 13 Creative Giving Options, Including Planned Giving