Supporting Sensory- Avoidant Children with Mealtime Challenges: Tips for a Positive Feeding Experience

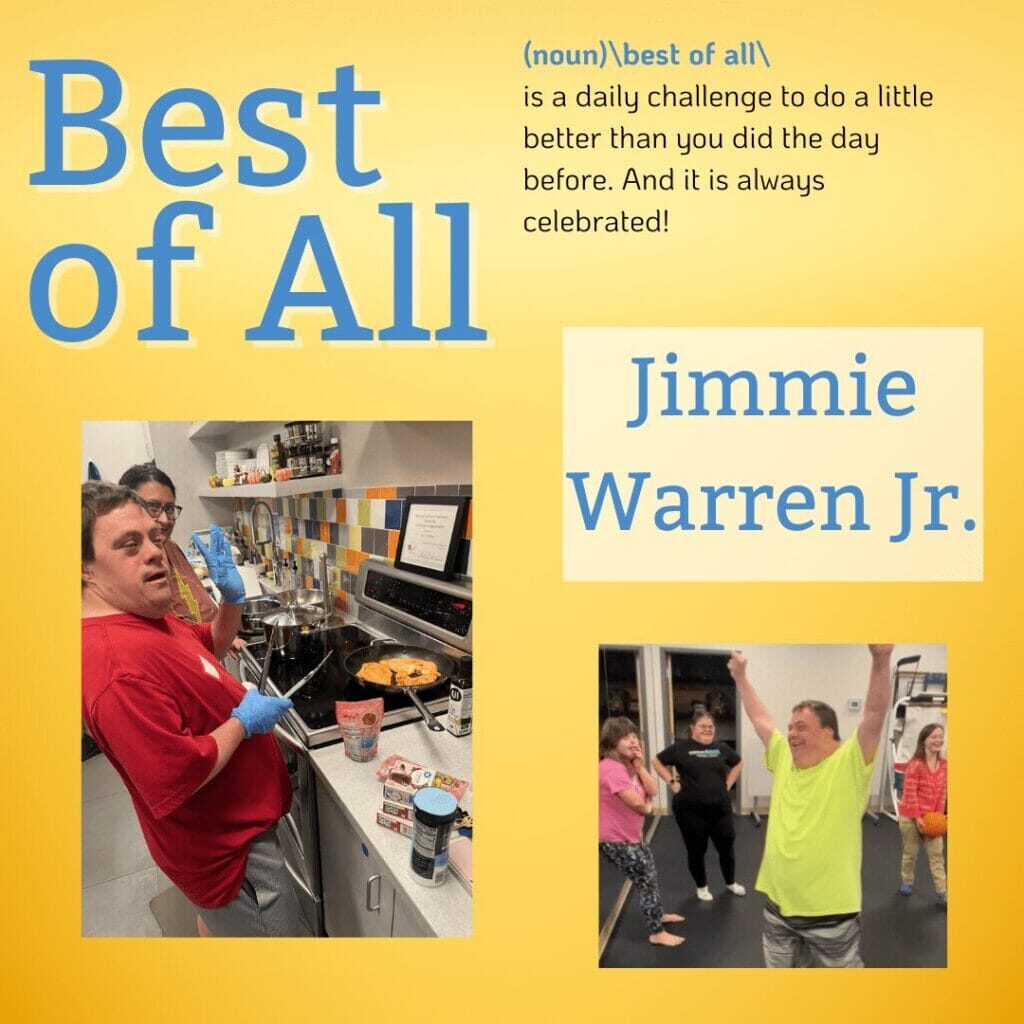

We’re delighted to give another warm welcome to our GiGi’s community! One of our biggest goals is to continue educating our community and others about Down Syndrome and how to enhance the lives of those with Down syndrome. A common trait while having Down syndrome is sensory sensitivities. This commonly impacts children’s responses to food textures, smells, and tastes. Understanding the logistics of this is crucial in helping your child enjoy food and having a positive feeding experience. We have recently had the pleasure of representatives from BayCare – Shea Kilby, Nayllim Rivera, and Rachel Doyle – visiting and sharing their knowledge, enlightening us about the importance of understanding feeding and sensory sensitivities.

Your child may be sensory avoidant, meaning that they have hyper- responsivity, which means they are over- aroused and avoid exposure to specific sensory inputs. They may also be sensory seekers, meaning they have hypo- sensitivity and are under- aroused, seeking exposure to specific sensory inputs.

Visual input significantly impacts feeding, where visual sensitivities may cause children to avoid foods based solely on their appearance, such as their color or the presence of mixed textures. Bright colors or too many items on a plate may be overwhelming and cause a child to lose interest in eating from the plate. To work with your child on this, begin with visual tolerance and tolerating food on the table. Once your child seems less overwhelmed with that, introduce them to tolerating the plate. It is also essential to encourage visual exploration of food; having them examine foods before touching or tasting them is beneficial, as it allows them to become accustomed to new foods before attempting to eat them. You should avoid surprises by introducing foods gradually and avoiding unpredictable and drastic changes in appearance.

Smell sensitivities also impact feeding, as children may gag or refuse to eat certain foods based solely on their smell. This sense is olfactory, being detected by receptors in the nose, and is closely related to the sense of taste. It is also connected to memory, emotion, and appetite, playing a significant role in food acceptance and aversion. Children may be sensitive to cooking odors or mixed food scents. They may also avoid new smells or ones that are overwhelming and strong. They may not want to eat these foods, even before seeing them, based on smell. To help with smell sensitivities, encourage smelling food from a distance first to get them used to it without getting overwhelmed. Having them smell foods from a distance applies less pressure to exposure, and it increases their comfort.

Auditory sensitives include sensitivity to volume, pitch, rhythm, and background noise; this sensitivity involves both external sounds and internal sounds (such as chewing and swallowing). If an individual is distracted or overwhelmed by sounds while eating, such as the sound of chewing and clanking dishes, they may avoid eating. Those with auditory sensitivities may avoid eating in generally loud environments, like a restaurant. Making mealtime quieter, using a calm voice, and minimizing background noise can be helpful for individuals with auditory sensitivities. It is also beneficial to introduce food sounds gradually.

Touch sensitivity is processed through the skin and the mouth, encompassing light touch, deep pressure, temperature, texture, and wetness. It is the foundation for food exploration and acceptance. Those who experience over- arousal may struggle with specific tactile sensations and avoid getting messy, preferring to use utensils to touch food rather than their hands. They may also dislike wet or sticky textures. Those who experience under- arousal may be unaware of the food in their mouth, often pocketing or overstuffing it. They may also be unaware that they are being messy.

Flavor sensitivities are influenced by smell, texture, and temperature. The five basic tastes are sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and savory. If someone experiences over- arousal to taste sensitivities, they may have a strong reaction to flavors. Those who experience under- arousal need strong flavors to notice and be aware. It is beneficial to build tolerance by exploring non- threatening tastes first, using curiosity rather than pressure. Using food chaining to introduce similar flavors and expand variety is essential.

There may also be hidden influences on feeding, such as proprioception or vestibular. Proprioception is body awareness, which supports posture, jaw stability, and self- regulation during meals. Vestibular function is related to balance and movement and is located in the inner ear. It also affects core stability, head control, and the ability to sit during meals. It is also linked to motion sensitivity and nausea. There may be difficulties sitting still during meals, including constant moving and fidgeting. Poor body awareness may also cause slouching, falling out of chairs, and messy self- feeding. Vestibular dysregulation may cause motion sickness, difficulty maintaining stillness, and a refusal to eat. It may also influence motor control and sensory modulation. Working on increasing strength, encouraging movement, and heavy work before or during feeding can help. Examples of this can include bouncing, deep pressure, pushing heavy objects, wobble seats, weighted vests, and fidget toys.

Food exploration should be a separate and prioritized activity apart from the typical structured mealtimes. This allows for a relaxed environment with no expectations for food consumption, removing pressure from the scenario and focusing on exploration and enjoyment. Familiar and new foods should be introduced, allowing for increased comfort with foods while also providing opportunities for play and tactile engagement with different textures. There should also be times for messy play with food. Ideas with this can include things like using stencils to make shapes with food, food art on placements, and squishing foods like a banana.

Providing mealtime structure is imperative for a child’s feeding, referring to the timing and location of feeding. Children have a better experience when there is repetition and consistency, as they gain an understanding of what to expect and what is expected of them.

The aspects of a mealtime schedule include:

- 3 meals scheduled per day at almost the same time every day

- Mid-morning and mid-afternoon snacks are recommended

- All-day snacking is not recommended

- Create a consistent, positive routine

- An idea to help your child is to provide a visual schedule with pictures of each step

- Seating your child in a highchair or chair with the least amount of distractions as possible (TV off and reduced background noise)

General Feeding Tips:

- Make gradual changes in the types of foods offered and how they are presented

- Avoid offering the same foods with the same presentation each time

- Changes can include the change of shape, color, texture, or taste of foods, or the brand of food, a different container, cup, or bowl

- Allow independence through giving your child choices at meals, such as picking between two possible food selections, or the type of utensil or dish used

- Allow your child to assist, such as setting the table, stirring, or pouring

- Give your child utensils even if they can’t feed themselves properly, potentially letting them feed you as well, and practicing turn-taking

- Allow your child to eat with their hands and get messy

- Avoid direct questions

- Ignore negative behaviors (things your child says or does that prevent pleasant mealtimes) because otherwise, your child learns that their negative behavior gets them extra attention, and mealtimes become unpleasant

- If your child does something you cannot ignore, reduce your reaction to it without showing any emotion to it, continuing if possible, and moving forward

- Teach your child positive alternative behaviors

- Use small steps, taking a step back when needed, but set specific requirements that may be a little easier

Developmental Stages:

- 0-13 months: Reflexive suckling occurs, which is the automatic suckling movement babies are born with to help them feed from the breast or bottle

- 4-6 months: Voluntary forward and backward suckling emerges, and suckling becomes more purposeful, allowing the child to control their tongue and move food or liquid to the back of their mouth. They eat thin- consistency pureed foods/ cereals at this stage.

- 6-7 months: The child learns to close their lips around a spoon and use suckling to pull food off. They eat thicker- consistency pureed foods at this stage.

- During this stage, sit face- to- face with your child and use a small, child- sized spoon, placing it at the center of your child’s lips. Apply gentle pressure to the tongue with the spoon and avoid scraping food off using your child’s lips or teeth. Wait for lip closure before removing the spoon.

- 7-8 months: Full tongue lateralization is developed, and your child can move their entire tongue side to side. At this stage, your child can eat soft, mashed table foods and explore hard munchables

- Soft mashed table foods are evenly mashed foods with no chunks

- Hard munchables are firm, safe foods that your child can mouth and explore, but not eat yet

- Hard munchables are used for exploration only at this stage

- While using hard munchables for sensory and oral motor exploration, they are also used to practice mouth and increase oral awareness, preparing the muscles needed for chewing without the pressure to eat (this should always be closely supervised)

- 8-9 months: Tongue tip lateralization is developed, allowing your child to eat meltable hard solids. Children can move just the tip of their tongue to the sides, helping with precise food movement and more control in chewing.

- Meltable hard solids are firm- textured foods that quickly dissolve with saliva, like baby puffs, teething wafers, or certain crackers

- These foods require little to no chewing or pressure

- Using these helps children get used to having solids in their mouths, being a positive introduction to solid foods, building oral motor skills, and preparing for more complex textures

- 9-10 months: The early chewing pattern of munching (moving their jaw up and down in a basic way) gets developed, and foods like soft cubes can be introduced. This is used to break down soft foods, but doesn’t yet involve side- to- side chewing.

- Soft cubes are small, soft pieces of food that break down into a puree when pressed with gentle up- and- down jaw movements

- Soft cubes allow for texture training, learning to manage soft solids in their mouth, building confidence, and developing basic chewing skills without needing full chewing strength yet

- 10-11 months: Rotary chewing emerges where your child begins to move their jaw in a circular or diagonal pattern, using the sides of their mouth to chew. This is a sign of more mature chewing skills, and they can eat single- textured soft mechanical foods at this stage.

- Soft mechanical foods are soft, easy- to- chew foods that break apart easily in the mouth, like pancakes or scrambled eggs

- Simple textures are foods that only have one texture throughout, making them easier to introduce to children first as they develop chewing skills and oral coordination, while not overwhelming your child

- 11-15 months: Development of consolidation of basic skills, where your child is integrating all the early feeding skills. At this stage, they can eat mixed- textured soft mechanical foods.

- Mixed textures are everyday table foods that combine more than one texture, such as hard textures with soft ones or liquids with solids, like soft- cooked pasta with sauce.

- Mixed textures require your child to eat more than one texture in one bite, building oral coordination, problem- solving during chewing, and preparing your child for family meals

- It may help to offer small bites and encourage your child to chew and explore different textures at their own pace

- 15-18 months: Development of tongue sweeping, which allows them to use their tongue to clean food off the sides of their mouth or gather food left behind, thereby helping with self- feeding and oral cleanliness. At this stage, they can eat hard mechanicals.

- Hard mechanicals are crunchy, firm foods that shatter or break apart when bitten, such as raw carrots or fruits

- Advanced chewing skills are required, where strong jaw strength, rotary chewing, and good oral coordination should be present already

Oral Motor Play Ideas:

- Chewing/Jaw Strength

- Fruit roll-ups, fruit leather, fruit chews, gum

- Make teeth marks on hard munchables like beef jerky or dried fruit

- Tug of war with licorice, playfully pulling on it as the child clenches their jaw

- Tongue Movement

- Singing “la la la”

- Licking popsicles or something sticky, like peanut butter, off a spoon

- Balancing a Cheerio on the tongue, stick the tongue in/out to play peek-a-boo

- Lip Movement

- Holding a Cheerio in the lips

- Using a kazoo or whistle

- Tightly holding a paper, object, or food between the lips

- Suckling

- Use a pacifier (4-12 months)

- Make a “fish face” and suck in your cheeks

- Hold a napkin on the bottom of the straw using only suction

When Should You Get a Feeding Evaluation?

- Gagging or vomiting during or after meals

- Coughing and choking during drinking or eating

- Difficulty gaining or maintaining weight

- Trouble transitioning to age- appropriate foods/ textures or utensils

- Negative behaviors at mealtimes

- Prolonged mealtimes (longer than 30 minutes)

- Reliance on caloric supplementation to meet nutritional needs

- Eating limited amounts

- Difficulty chewing or food loss

- Avoiding/leaving out certain food groups or textures

- Requiring the TV or other distractions to eat

A child experiencing feeding difficulties can make mealtimes unpleasant and stressful for everyone involved. Mealtimes can be challenging for families, but it is essential to acknowledge the positives in the situation and make informed decisions to move forward. Focus on what went well and what you learned during mealtimes or food play times, rather than just the challenges. Taking what you learned and applying it will only improve your experience and your child’s experience. Celebrate both the big and small steps. Shifting your mindset can help make this experience more positive rather than negative, keeping your goals in mind and fostering your child’s growth.

Be sure to check out our programs calendar on our website to register for the next Family Speaker: Parent University Program night. This program is every fourth Wednesday of every month from 7:00- 8:30pm. It is held both virtually, as well as in- person at the Tampa Playhouse. https://gigisplayhouse.org/tampa/sfcalendar/

Recent Posts